Measuring UNICEF’s ‘whole school approaches’ to child rights education

by Marie Wernham

1. Introduction

‘After 16 years as a head teacher I cannot think of anything else that we have introduced that has had such an impact.’ But how can we prove it?

UNICEF defines child rights education (CRE) as: ‘teaching and learning about the provisions and principles of the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) and the “child rights approach”* in order to empower both adults and children to take action to advocate for and apply these at the family, school, community, national and global levels.’** CRE takes place in many contexts, for example with professionals, parents and caregivers, policy-makers and the general public. However, this article is concerned with CRE in formal education settings such as early childhood education, primary and secondary schools.

* The child rights approach is one that: furthers the realization of child rights as laid down in the CRC and other international human rights instruments; uses child rights standards and principles from the CRC and other international human rights instruments to guide behaviour, actions, policies and programmes (in particular non-discrimination; the best interests of the child; the right to life, survival and development; the right to be heard and taken seriously; and the child’s right to be guided in the exercise of his/her rights by caregivers, parents and community members, in line with the child’s evolving capacities); builds the capacity of children as rights-holders to claim their rights and the capacity of duty-bearers to fulfil their obligations to children. UNICEF Child Rights Education Toolkit: Rooting Child Rights in Early Childhood Education, Primary and Secondary Schools, First Edition, UNICEF, Geneva 2014, p.21.[Hereinafter: UNICEF CRE Toolkit].

** Ibid, p.20.

|  |  |  |

|---|---|---|---|

|  |

Common sense dictates that children who witness and experience respect for their rights on a daily basis will better understand and act on these rights than children who simply hear about child rights as part of a one-off lesson plan. UNICEF is therefore encouraging its National Committees* (offices operating in higher income countries, where much of this work is evolving) where possible to move towards ‘whole school approaches’ to CRE. Whole school approaches aim to bring about a fundamental transformation in the school environment by embedding child rights into the everyday management, functioning and atmosphere of the school, particularly regarding relationships amongst adults, amongst children, and between adults and children. Manifestations of this may vary according to local contexts, but whole school approaches have certain principles in common: schools should be inclusive, child-centred, democratic, protective and sustainable and they should actively promote and implement the child rights approach and the provisions and principles of the CRC. There is no single model for developing a whole school approach to CRE but the most well-known include UNICEF’s child-friendly schools, UNICEF’s rights respecting schools and Amnesty International’s Human Rights Friendly Schools. UNICEF National Committees are finding the rights respecting schools model the most appropriate as a basis for adaptation and it is therefore this model which is most frequently referred to in this article.

* ‘The National Committees are an integral part of UNICEF’s global organization and a unique feature of UNICEF. Currently there are 34 National Committees in the world, each established as an independent local non-governmental organization. Serving as the public face and dedicated voice of UNICEF, the National Committees work tirelessly to raise funds from the private sector, promote children’s rights and secure worldwide visibility for children threatened by poverty, disasters, armed conflict, abuse and exploitation.’ UNICEF website, accessed 26 November 2015.

There are currently ten UNICEF National Committees engaged in whole school approaches to CRE, reaching a combined total of almost 1.4 million children in about 4 000 schools: Denmark, France, Germany, Greece, Iceland, Italy, Slovakia, Spain, Sweden and the UK. Most of these are in the UK which has the longest-running programme.

Anecdotal evidence from children, teachers and head teachers, parents and local education authorities alludes to the positive impact of these whole school approaches to CRE.

‘We know how to respect each other…we actually know why and how we are respecting that person, we are listening to what they are telling us, we are being kind to everyone. It’s pretty awesome.’ (Girl, Canada, on what it means that her school has adopted a whole school approach to CRE).*

* CRE Tookit, p.37.

‘After 16 years as a head teacher I cannot think of anything else that we have introduced that has had such an impact.’ (UK head teacher).*

* Ibid, p.73.

‘My daughter has taken a lot of it on board and is growing into a really, really impressive individual. As a parent, this is the first place that I’ve felt really comfortable […] I think all nurseries should have to do it.’ (Parent, UK).*

* Ibid, p.40.

2. Proving the impact more systematically: Monitoring and Evaluation Methods

But how can this be proved more systematically? The child rights approach implies that the process of doing something is as important as the outcomes. How, therefore, does this apply to the monitoring and evaluation of these whole school approaches? What are the methods and criteria used? How do these translate across different national and local contexts? What are the lessons learned and the gaps identified in this relatively young yet evolving field?

Monitoring and evaluation methods tend to include the usual array of qualitative and quantitative tools such as surveys, focus group discussions, interviews and desk reviews of data and documents. In relation to school-level monitoring and evaluation, general guidance is provided by the UNICEF National Committee in the form of standardised criteria and methodology, but decisions on exactly what to measure are taken at the local level, often by panels of mixed children and adults. They decide what matters and how best to measure it. Successful implementation of a whole school approach to CRE requires an emphasis on participatory processes and collaborative journeys, involving all relevant stakeholders, rather than racing to tick off a checklist of pre-determined achievement criteria.

For example, Riverbank School, a primary school in Scotland, which has been involved in UNICEF UK’s Rights Respecting Schools Award (RRSA) for over 7 years, adapted their understanding of the RRSA concepts to fit with the Scottish government national approach to improving the well-being of children and young people in Scotland, known as ‘Getting it right for every child’ (GIRFEC).* Riverbank School links the eight GIRFEC indicators** to the CRC: ‘Our vision is to have a school where all “Learn together, Play together, Achieve together” and to promote the […] CRC.

* The Scottish Government website, accessed 26 November 2015.

** The Scottish Government website, accessed 26 November 2015.

Eight words describe what things look like when it’s going well – safe, healthy, achieving, nurtured, active, respected, responsible and included. They are sometimes referred to as “indicators of well-being”. How well do you think we are doing?’ They developed a set of simple questionnaires for students and parents based on a Likert scale ranging from ‘strongly agree’ to ‘strongly disagree’ (and ‘don’t know’), responding to the following types of statements:

-

Safe (CRC Articles 38; 37; 11; 32; 22; 19; 33; 34; 35; 36): I feel safe at school; If I don’t feel safe, I know who to go to for help; I know what to do if I’m worried about myself or someone else.

-

Healthy (CRC Articles 3; 39; 24; 6): People at school help me make healthy choices; At lunchtime I can enjoy healthy food in a friendly environment; I can learn about healthy lifestyles, including thinking about my feelings and relationships.

-

Achieving (CRC Articles 18; 29; 4; 28): I am encouraged to learn and do my best at school; I get a chance to talk about what I like to do at school and the things I’ve achieved outside school; I get a chance to share and celebrate my achievements.

-

Nurtured (CRC Articles 18; 5; 20; 21; 25; 27; 4): I know that people care about me at this school; When I have a problem, I know how to get help; My teacher knows me well as an individual.

-

Active (Articles 31; 23; 3): I can plan my learning and make choices about how I learn) I get a chance to take part in regular physical exercise; I get a chance to share my learning to show my understanding and achievements.

-

Respected (CRC Articles 18; 13; 14; 3; 8; 1; 16; 5): People take time to listen to what I have to say; I get a chance to say what I think and contribute to decision-making in my class and school; My views are taken into account and lead to changes; I learn about UNCRC and about respecting the rights of others.

-

Responsible (CRC Articles 3; 40; 12; 14; 15): I am clear about expectations for my behaviour and my part in making it positive for everyone; I understand what I’m learning about at the moment, and what I’ll be learning next; I get a chance to help others and take on leadership roles through committees.

-

Included (CRC Articles 26; 4;3; 27; 28; 29; 23; 2; 18; 6) I feel I belong in my class, school and community; I know I will get support when I need it; I can help others in my school to make sure they feel included in play and learning.

Students are also asked: ‘Can you tell us what makes a good lesson?’, ‘Which rights are important to you?’ and ‘Other comments’.*

* Adapted from the table format of the ‘Pupil Questionnaire’ by Riverbank School, Scotland, 2014. A similar version for parents exists, based on the same eight concepts.

3. Variations in the processes from country to country

This is just one example of what a tool might look like in practice. Processes vary from country to country, but a school embarking on the journey towards a whole school approach may well convene a steering group of mixed child and adult representative stakeholders to oversee the programme, involving, for example, students, teachers, non-teaching staff (such as administrators, caterers and playground supervisors), parents and members of the governing board. Some countries specify that children should make up 50 % of the steering group. This steering group works together to conduct a baseline study on the status of child rights implementation in different aspects of school life. These aspects could include for example, knowledge attitudes and practice of children and adults and an audit of existing records (for example levels of attendance, staff sick leave, behaviour warnings and incidents of violence). The steering group will discuss and decide which aspects to focus on and how best to measure them, guided by the sample UNICEF tools.

The baseline study then forms the basis of a collaboratively designed school action plan. The steering group is then likely to conduct annual reviews using similar tools to assess progress. In some countries the whole school approach is run as an award scheme where the school works towards achieving certain standards, resulting in some form of certification, recognition or branding as (for example) a ‘UNICEF Rights Respecting School’. In these cases, there is likely to be an external evaluation conducted by UNICEF National Committee staff, partner NGOs, local education authorities or even peer review by other, more experienced schools.

For example, the UNICEF UK RRSA has four standards which are listed here:

-

Standard A - Rights-respecting values underpin leadership and management: The best interests of the child are a top priority in all actions. Leaders are committed to placing the values and principles of the Convention at the heart of all policies and practice.

-

Standard B - The whole school community learns about the Convention [on the Rights of the Child]: The Convention is made known to children and adults who use this shared understanding to work for global justice and sustainable living.

-

Standard C - The school has a rights-respecting ethos: Young people and adults collaborate to develop and maintain a rights-respecting school community in all areas and in all aspects of life based on the Convention.

-

Standard D - Children are empowered to become active citizens and learners: Every child has the right to say what they think in all matters affecting them and to have their views taken seriously. Young people develop their confidence through their experience of an inclusive rights-respecting school community, play an active role in their own learning and speak and act for the rights of all to be respected locally and globally.

More detailed criteria exist for what these look like at Levels 1 and 2 of the award.

There are also three stages: Recognition of Commitment (where schools develop an action plan and procedures for monitoring impact), Level 1 (an interim step where schools show good progress towards achieving full RRSA status) and Level 2 (where the school has fully embedded the values and principles of the CRC into its ethos and curriculum and can show how it will maintain this). The school self-evaluates progress against the Level 1 and 2 standards and, when they believe they have met them, an external assessment by UNICEF UK takes place resulting either in accreditation or further guidance. A follow-up takes place by UNICEF UK 3 years after a school has achieved Level 2 to ensure that standards are being maintained. In the Slovakian model schools work towards obtaining a certificate by fulfilling a set of criteria established by UNICEF Slovakia. Part of the assessment process requires that students evaluate their school’s progress and communicate this information directly to the UNICEF Slovakia programme coordinators, without it being filtered through adult intermediaries. After 2 years of being a Rights Respecting School the school takes a more individual path, setting their own goals and actions to be taken for the next period.

In addition to the monitoring and evaluation of individual schools’ progress, UNICEF National Committees also conduct assessments and evaluations of their programmes as a whole. For example, UNICEF Germany is currently working with a university Masters student to conduct an in-depth evaluation together with students in two schools. UNICEF UK conducted a survey of 300 head teachers in 2014 and noted the following impacts: 99 % of head teachers report that RRSA has had a positive impact on relationships and behaviour; 99 % of head teachers report that the RRSA contributed to children and young people being more engaged in their learning; 98 % report that RRSA impacted on children and young people’s positive attitudes to diversity and overcoming prejudices; 96 % report that working on RRSA improved children’s and young people’s respect for themselves and others; and 75 % report that RRSA has had a positive impact on reducing exclusions and bullying. An external evaluation of UNICEF UK RRSA programme by the Universities of Sussex and Brighton in 2010 found that the RRSA ‘has had a profound effect on the majority of the schools involved in the programme. For some school communities, there is strong evidence that it has been a life-changing experience.’*

* Sebba, Judy and Carol Robinson, Evaluation of UNICEF UK’s Rights Respecting Schools Award: Final report, September 2010, UNICEF UK, London, 2010, p.3 UNICEF website, accessed 20 October 2015.

National Committees are supported by UNICEF headquarters in Geneva. An annual review process takes place between the National Committees and UNICEF in Geneva in relation to the National Committees’ overall planning strategies and progress towards stated objectives. Given the diversity of National Committee contexts these strategies are not yet standardised but efforts are being made to improve the ‘SMART’-ness* of indicators in relation to whole school approaches to CRE. UNICEF in Geneva is in the process of developing some standardised, overarching indicators for whole school approaches to CRE, amongst other things.

* Specific, Measureable, Attainable, Realistic and Time-bound.

4. Lessons Learned

The following lessons have been learned in relation to monitoring and evaluating whole school approaches to CRE:

-

Guiding questions, templates and examples can be useful but respect for the principle of participation requires enough flexibility for stakeholders to adapt things according to their own realities, without deviating too far from the overarching principles;

-

There is a need for improved indicators and methods to measure impact rather than just progress of the initiative;

-

Much of the monitoring and evaluation in this area focuses on changes in the behaviour of children as a result of the initiative. However, in order to avoid the initiative being misunderstood as being a way to ‘control’ children’s behaviour there needs to be better measurement of behaviour change also in duty-bearers such as teachers, non-teaching staff and parents.

As this is still a relatively young field, there is still a long way to go to perfecting frameworks, tools and approaches and the following gaps are noted:

-

There is a need for more in-depth evaluations from more countries;

-

Longitudinal research that looks at the longer term impacts and checks whether gains are maintained across transitions between levels of schooling and school-leaving is required;

-

Policy advocacy would benefit from better measurement of if and how whole school approaches to CRE impact on academic achievement.

Although improvements can always be made, it is nonetheless encouraging to note in general the application of the child rights approach to the monitoring and evaluation process. This is seen in particular in the following aspects: the participation of children in the process (designing, conducting, responding to and analysing research); non-discrimination (efforts are made to not just work with the most articulate, confident children); considering the best interests of the child as a guiding principle; involving parents and communities; and maintaining the overall aim of ensuring the best possible opportunities for children’s development to their fullest potential.

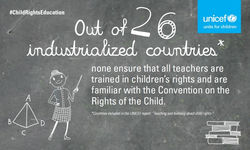

Finally, it is worth putting this work into the broader context of CRE implementation in formal education settings at national level. In 2014-2015 UNICEF commissioned the Centre for Children’s Rights at Queen’s University Belfast to conduct research on implementation of CRE in 26 industrialised countries. The online survey component focused on measuring five aspects of CRE based on a wide-ranging desk review on child and human rights education: Is there a requirement in the curriculum for all children to learn about child rights? Does the government, or a public agency, monitor/inspect the quality of CRE? Are all teachers trained in children’s rights and the CRC as part of their initial training? Do the regulations concerning who is qualified to teach refer to child rights? To what extent are schools required to run student councils?

The online survey was completed by 88 in-country experts across the 26 countries. The responses were triangulated and enhanced with additional desk research, resulting in brief country summaries and a comparative table mapping the key results. For example, in 15 out of the 26 countries participating in this research (58 %), there is no entitlement in the official curriculum for all children to learn about children’s rights. None of the 26 countries ensures that all teachers are trained in children’s rights and are familiar with the CRC. CRE is explicitly and consistently monitored in only three out of the 26 research countries (12 %). Whilst opportunities for children’s participation in decision-making in school are widespread, it falls short of an entitlement in most countries. Only four countries (15 %) judged school councils to be fully or almost fully implemented across the country.

The online survey was supplemented by seven more in-depth country case studies, one of which (Scotland) focuses particularly on the whole school approach to CRE. Scotland’s country case study illustrates how UNICEF UK is developing policy alignment in the Scottish education system through promoting coherent connections between central government, local government and schools. The research project overall led to the identification of benchmarking statements in the following areas which will help to inform further work on CRE implementation: official curriculum, teacher education, resources, pedagogy, policy alignment across the education system, participation as a right, and monitoring and accountability.

In conclusion, just as the schools go on a journey to implement a whole school approach to CRE, so too are UNICEF and its National Committees on a journey to improve how they measure the impact of this important initiative. It is important to measure what matters, not just in order to improve programming and to support evidence-based advocacy, but ultimately to accelerate implementation of the CRC, the most comprehensive and widely ratified human rights instrument in the world, ‘considering that […] recognition of the inherent dignity and of the equal and inalienable rights of all members of the human family is the foundation of freedom, justice and peace in the world’ and that ‘the child should be fully prepared to live an individual life in society and brought up in the spirit of […] peace, dignity, tolerance, freedom, equality and solidarity’.* A whole school approach to CRE increasingly appears to be an excellent way to achieve this ideal.

* United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, ratified 20 November 1989, entered into force 2 September 1990, Preamble. United Nations Human Rights website accessed 19 October 2015.

For more information, including copies of the UNICEF CRE Toolkit and the research study ‘Teaching and Learning about Child Rights: A study of implementation in 26 countries’, see: UNICEF website.

Author

Marie Wernham is an independent international child rights consultant currently based in France. She has worked in over 30 countries with children, NGOs, UNICEF and the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child. One of her current roles is Child Rights Education Consultant, UNICEF, Private Fundraising and Partnerships Division (Geneva).